TRIJŲ KRYŽIŲ KALNAS

Kryžių istorija siejama su kunigaikščio Gedimino ketinimu pakrikštyti Lietuvą. Gediminas 1341m. iš Čekijos pasikvietė vienuolių pranciškonų. Perversmo metu, kurį vygdė kunigaikščio politiniai oponentai, buvo išžudyti ir į Vilnių atvykę pranciškonai. Vienuolių kankinių atminimui spėjamoje jų palaidojimo vietoje, Plikajame kalne, buvo pastatyti mediniai kryžiai. Medinių kryžių vietoje, šiems sunykus, iškildavo kiti.

1916m. architektas Antanas Vivulskis sukūrė projektą ir už miestiečių slapta paaukotas lėšas pastatė naujus betoninius kryžius. 1950m. gegužes 30d. sovietinės valdžios įsakymu paminklas buvo susprogdintas. Beveik po 40metų -1989m. birželio 14d. - Lietuvos persitvarkymo sąjūdžio iniciatyva, paminklas buvo atstatytas.

Pagal laikraščio "15min" rubriką.

THE THREE CROSSES

The history of the Three Crosses dates back to Gediminas, the Grand Duke of Lithuania, and his intention to christianize the country. In 1341, Gediminas invited Franciscan monks from what is now known as the Czech Republic to come to Vilnius. During the takeover, which was organized by the Duke's political enemies, the monks were among the many slaughtered. Thus, they became martyrs and in their memory, wooden crosses were erected on the Grey Hill, where they were supposedly buried. As some crosses decayed, others rose...

In 1916, the architect Antanas Vivulskis came up with a project, secretly funded by the town dwellers' generous donations, to build new concrete crosses on the top of the hill. In may 30 of 1950, by order of the Soviet authorities, the monument was demolished. Almost 40 years later, in june 14 of 1989, with the Reform Movement of Lithuania, the monument was restored and stands still today.

Extract from a column in "15min".

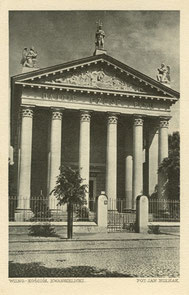

Vilniaus Švč. Trejybės Graikų apeigų katalikų bažnyčia

Stačiatikiai buvo pirmieji krikščionys, kuriuos pažino LDK valdovai pagonys, jų įtaka politiniame gyvenime buvo itin svari. Stačiatikiai tapo ir pirmaisiais krikščionimis savo

kankinyste paliudijusiais tikėjimo tvirtumą. Visgi konfesinis apsisprendimas, išreikštas katalikų krikštu 1387 m., nulėmė provakarietišką orientaciją, kuri laikui bėgant tapo esmine kratantis

stiprėjančios Maskvos įtakos.

Po krikšto, stačiatikių, sudariusių LDK valstybės gyventojų daugumą, politinis ir socialinis statusas smarkiai pasikeitė. Tik patys galingiausi stačiatikiai didikai buvo įsileidžiami į

politinio elito gretas. Tačiau siekiant išlaikyti įtaką Rytų žemėse (dabartinėje Baltarusijoje, Ukrainoje), kuriose stačiatikybė buvo dominuojanti religija, LDK valdovai sąmoningai laikėsi

prostačiatikiškos politikos. Toks dvigubas konfesinis žaidimas lėmė dviejų krikščionybės šakų gyvavimą greta vienoje valstybėje. Ši dviejų religinių tradicijų sąveika bei bajorijos

politiniai-socialiniai integraciniai procesai palaipsniui atvedė prie bažnytinės unijos projekto įgyvendinimo – 1596 m. paskelbta Brastos bažnytinė unija. Pagal ją sukurta nauja krikščioniška

konfesija – unitai, vėliau imti vadinti graikų apeigų katalikais. Unitai išreiškė dviejų senųjų krikščioniškų religijų sintezę – jie pripažino Romos popiežiaus viršenybę bei svarbiausias katalikų

dogmas, tačiau išsaugojo savitą per 500 metus Kijevo Bažnyčioje susiformavusią liturgiją, tradicijas ir gimtąją ukrainiečių kalbą. Užsitikrinę valdovo protekciją, graikų katalikai pagal

skaitlingumą bei įtaką veikiai tapo antrąja konfesija Vilniuje ir visoje LDK. Tuo tarpu Vilnius tapo svarbiausiu unitų religiniu centru. XVII a. vid. graikų katalikų metropolitas savo rezidenciją

galutinai perkėlė į Vilnių.

Vilnius St.Trinity Greek Catholic Church

Orthodox christians were the first christians that the pagan rulers of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania had met. Their influence in the political life of the Duchy was great. Orthodox christians were also the first christians who verified the strength of faith by their martyrdom. However, the christening of the Grand Duchy to Catholicism in 1387, meant that eyes turned to the West, particularly with the growing threat from Moscow.

After the christening, the political and social status of Orthodox christians, who formed the majority of the population, changed. Only the most powerful Orthodox christian noblemen were now welcome in the ranks of the political elite. Nevertheless, in order to maintain the grip on the eastern territories (present Belarus and Ukraine), where Orthodox christianity dominated, the rulers of the Grand Duchy had to lead friendly politics towards Orthodox christians. Such game of duplicity determined the coexistence of two branches of Christianity in one state. This interaction of the two religious traditions and the political social integration processes of the nobility gradually led to the realization of the Union of Brest in 1596. A new confession was created - the Ukranian Greek Catholic Church. It expressed the fusion of the two oldest Christian religions by recognizing the Roman Catholic Pope as well as the fundamental Catholic doctrines, but preserving a unique liturgy, nurtured for 500 years in the Church of Kiev, its traditions and the Ukranian language. Because of their numbers and influence, having gained the protection of the ruler, the Ukranian Greek Catholics swiftly became the second confession in the whole Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Vilnius became their primary religious centre and in the mid. XVII century, the Ukranian Greek Catholic metropolitan bishop moved his residence there.